Why do we sometimes falter at even the simplest of tasks? A new study from the lab of MCB Professor Florian Engert suggests that lapses in focus, rather than a lack of ability, may be the key driver. By analyzing the behavior of larval zebrafish, Kumaresh Krishnan, a former PhD student in Engert’s lab, uncovered evidence of attentional “switching”—a process that could offer fresh insight into how brains balance priorities and maintain competence.

The research explores the optomotor response (OMR), a well-established behavioral test. In the OMR, zebrafish swim in the direction of moving visual stimuli, a strategy that helps them orient in currents or follow other fish. Because the task is simple and robust, scientists assumed that fish would nearly always perform it correctly. But Krishnan noticed something surprising.

“One would expect that a simple task like this, they would be close to 100% in how they solve it,” Krishnan explained. “But we do notice that they make some errors. What we’ve come to find is that a lot of this can be attributed to not caring about the stimulus at certain points in time. Maybe they’re focused on some other priority.”

In other words, the mistakes weren’t necessarily due to a failure of perception or motor control. Instead, the fish seemed to disengage. By modeling this behavior, Krishnan and colleagues showed that performance could be divided into two distinct states: an “engaged” state, in which fish performed the task almost flawlessly, and a “disengaged” state, in which their responses fell to chance.

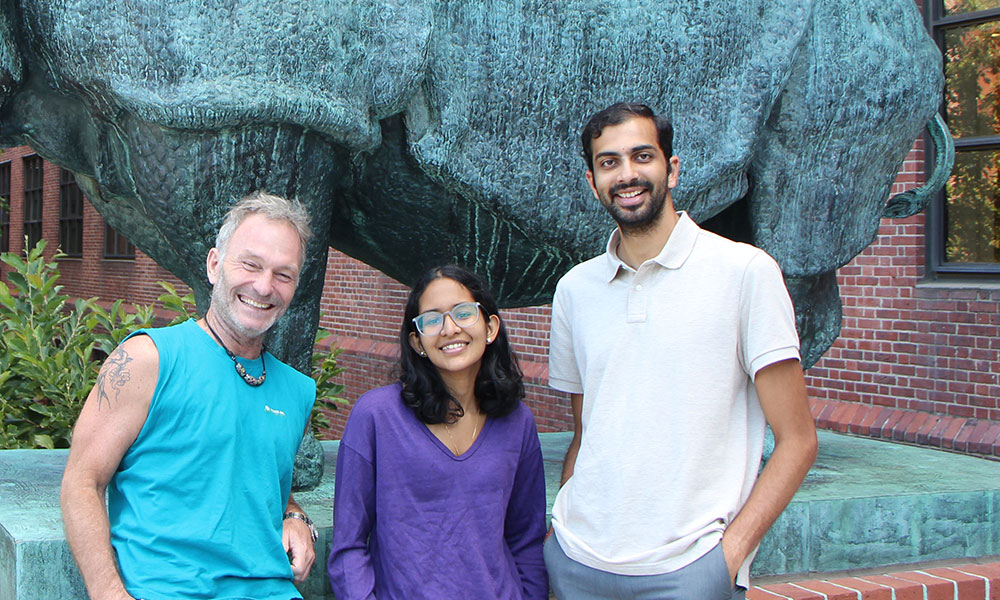

The clarity of the results struck Engert as a transformative moment for his lab. “There was one dramatic and pivotal and catalytic event in my scientific journey over the last fifteen years – and that was when Kumaresh showed me the first complete data set on zebrafish performance in the OMR task,” Engert recalled.

“We suddenly saw that the ‘behavioral performance cloud’ could be segregated into one portion where the fish performed almost perfectly, and another one where they performed at chance levels,” he adds. “The two datasets were easy to distinguish. It basically jumped out at you from the page. And it truly gave the game away – and it was only possible because Kumaresh had collected and analyzed the data already in a fashion that made it easy to isolate the inattentive swim bouts from the attentive. It’s one of the best examples to illustrate the power of having a model and a hypothesis. It was transformative, and without Kumaresh, this epiphany wouldn’t have been possible.”

To capture these behavioral states, the team used a computational framework that combined a Hidden Markov Model with a Drift Diffusion Model, both commonly employed in decision-making research. This allowed them to define two orthogonal descriptors of performance: how often a fish is engaged (focus), and how well it performs when engaged (competence).

Intriguingly, Krishnan found that these two dimensions could be teased apart experimentally. Zebrafish bred and raised in different facilities showed distinct patterns. “More often than not, the parental contribution seems to determine how often they’re attentive, while the environment plays a greater role in determining how well they perform when engaged,” he said. “Blame your parents if you can’t pay enough attention. Blame your environment if you can’t do well when you’re paying attention.”

Though partly tongue-in-cheek, this observation hints at a deeper truth: genetic and epigenetic factors may shape baseline attentional engagement, while environmental context tunes task competence. If verified, this framework could help neuroscientists dissect how brain circuits regulate attention and how these circuits interact with inherited and environmental influences.

For Krishnan, who has since moved on to computational biology research with Sean Eddy, the work opens multiple next steps. “One of the next steps is to really unpack this parental versus environmental contribution with some very dedicated perturbations,” he said. “A slightly longer-term thing would be to look at diet—if parental diet influences offspring attention, that would be fascinating at the genetic or epigenetic level.”

The broader goal is to identify the neural circuits underlying these behavioral states and, eventually, understand whether attention can be manipulated.