A long-standing mystery in microbiome research—how a gut-bacterial toxin physically damages human DNA—has finally been solved through a close collaboration led in part by researchers in the Victoria D’Souza Lab at MCB. The discovery, published December 4 in Science, provides the first direct structural view of the covalent link between the two DNA strands, which is mediated by colibactin, a DNA-damaging small molecule produced by certain E. coli species in the gut microbiome that has been linked to colorectal cancer development, including early-onset cases.

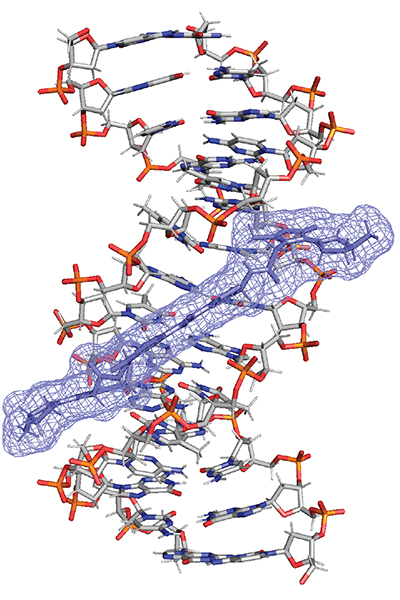

Cartoon representation of the interaction showing the placement of colibactin and its molecular surface (purple mesh) inside the minor groove of DNA (grey and red).

For years, researchers have known that colibactin causes dangerous DNA lesions, but its chemical instability has made the structure of its DNA bound state difficult to capture. Without that structure, scientists lacked a fundamental understanding of how the toxin selects specific genomic sites and why its mutational “signature”—several As and Ts in a row from the repair of colibactin-induced double-strand breaks—repeatedly appears in tumor genomes.

The new study solves that problem by combining three highly specialized approaches: microbial chemistry in the Chemistry and Chemical Biology (CCB) lab of Emily Balskus, high-resolution NMR spectroscopy in the D’Souza Lab, and advanced mass spectrometry in collaboration with the Silvia Balbo Lab and Peter Villalta at the University of Minnesota.

Balskus, who spearheaded the project, noted the impact of finally capturing the structure of the colibactin lesion. “We have had to be creative in our efforts to understand its chemical structure and biological activity,” she says. “This work determines the specificity of colibactin for DNA crosslinking and the detailed structure of the lesion. It reveals the structural basis for colibactin’s activity and explains the locations of mutations in the genome linked to colibactin exposure.”

The interest in colibactin originated from Balskus’s lab’s longstanding efforts to understand this gut bacterial toxin. Their expertise in microbial chemistry enabled the biochemical elucidation of colibactin’s sequence-, groove-, and atomic-specificity. “Yet the biochemical data left unanswered questions about colibactin’s central structural motif and its non-covalent interactions with DNA,” explains co-first author Erik Carlson, a former postdoctoral fellow of the Balskus Lab. “That’s where Dr. D’Souza’s lab really shined—using biomolecular NMR to clarify features that couldn’t be resolved any other way.”

“The structure we solved shows how colibactin recognizes very specific DNA sequences,” adds co-first author Raphael Haslecker of the D’Souza Lab. “Only AT-rich regions allow it to sit in exactly the right orientation long enough to form the crosslink. That sequence preference is so strong that the producing bacteria rarely contain the motifs colibactin targets.”

Haslecker also confirmed the existence of a long-suspected but unproven chemical feature: a positively charged nitrogen at the molecule’s center. This unstable motif can survive only when the toxin is tucked inside DNA. The finding helps explain both colibactin’s reactivity and why it has been so challenging to study for more than a decade.

“It truly took a proverbial village to resolve the unanswered questions in the field,” says D’Souza. “Erik first overcame the major obstacle of generating sufficient material for structural studies. Raphael then took on the structure determination, which was particularly challenging both because of the pseudosymmetric nature of colibactin and because the samples contained both colibactin-bound and unbound DNA, which substantially increased the spectral complexity”.

Carlson and Haslecker also highlighted the synergy among all teams involved, including computational input from colleagues in MIT’s Kulik Research Group. “These groups met constantly,” Carlson said. “Being less than five minutes apart made it incredibly easy to share results and troubleshoot in real time.”

As Haslecker put it, “These complementary expertises were essential to solving a conundrum that had eluded the field for years.”