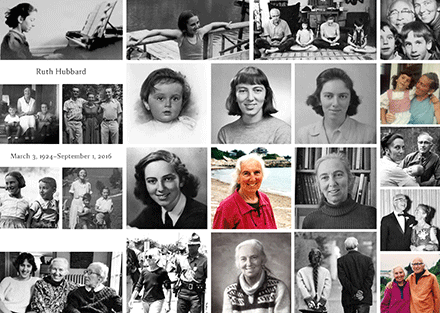

Professor Ruth Hubbard Wald, prominent biochemist, feminist, and the first female biology professor to be awarded tenure at Harvard University, died Sept. 1st at her home in Cambridge at the age of 92.

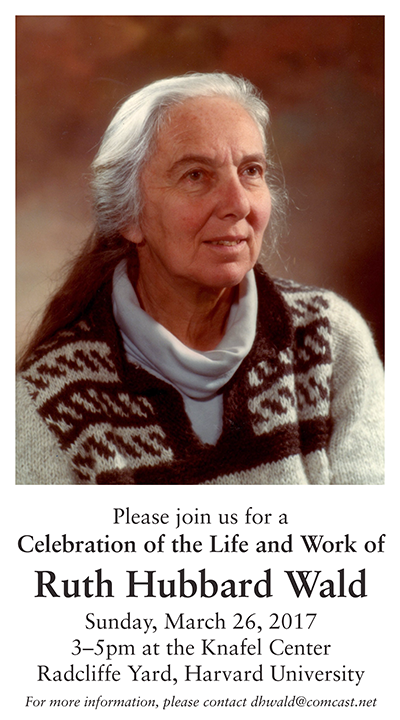

A memorial event will be held on March 26, 2017, at 3 pm at the Knafel Center in Radcliffe Yard at Harvard.

Professor Hubbard was born in 1924 in Vienna, Austria, where both her parents, Richard Hoffmann and Helene Ehrlich Hoffmann, were physicians and socialists. They moved the family and the teenaged Ruth to the US in 1938, after Nazi Germany annexed Austria.

Hubbard earned her Ph.D. in biology from Radcliffe College in 1950, where she also earned her A.B. and met her first husband Frank Hubbard. She met her second husband, Professor George Wald, when she came to Harvard after World War II.

Hubbard’s early research focused on vision in both vertebrates and invertebrates, which she studied with Wald.

“Ruth Hubbard was a superb scientist who contributed substantially to our understanding of photoreceptors and their light-sensitive visual pigment molecules,” said Professor John Dowling, a former colleague of Hubbard’s and current Professor of Neurosciences at MCB. “As a graduate student, Ruth worked out the enzymatic conversion of vitamin A to vitamin A aldehyde, now called retinal, the light-sensitive component (chromophore) of all visual pigments.”

“A second important project she carried out was to show that the visual pigment protein, opsin, is much less stable when the retinal chromophore is not attached to opsin forming a visual pigment,” Dowling said. “This suggested why in vitamin A deficiency, when there is lack of retinal in the eye, the photoreceptors which house the visual pigments degenerate.”

Dowling said a third valuable study conducted by Hubbard involved the effects of light on visual pigments. Her partner in this research was Professor Alan Kropf, who came to the Wald lab as a postdoc in 1956. In an essay written in honor of Hubbard’s appointment as Professor Emerita in 1990, Kropf described her as an exacting mentor.

“She was an intellectually demanding critic but an enthusiastic supporter of my fumbling efforts to learn about visual pigments, from the details of how to cut open an eye, to how to interpret an experiment, to how to draw a figure for a paper which forcefully presented the idea we were trying to get across,” Kropf wrote.

Hubbard was awarded tenure at Harvard in 1974, but by that time her focus had shifted from science to politics. By that time she was an ardent feminist and anti-war activist, who also argued in favor of increasing diversity in scientific research. She believed that women and minorities should be encouraged to become researchers not only for reasons of social fairness, but also to encourage scientific rigor and avoid the social bias of research done only by white men.

“She translates thought into action,” wrote her friends, Dr. Alan Steinbach and his wife Sala, in an essay titled “In Celebration of Ruth Hubbard.” “I think, Ruth said, we should picket our own post office to demonstrate our opposition to the draft…two weeks later, there we were. Ruth has that effect.”

Hubbard’s former colleague in the Harvard Biology Department and current Washington University professor Ursula Goodenough wrote about how her own political ideas were influenced by Hubbard in 1970, when she was invited to Hubbard’s house to participate in discussions on feminism.

“Ruth brought us all together, held us together, and in many different ways became the catalyst and touchstone for our emerging feminism, she of course always being way ahead of the rest of us,” Goodenough wrote.

Hubbard wrote about her ideas on the role of women in science in the books The Politics of Women’s Biology and Profitable Promises: Essays on Women, Science & Health. She also co-wrote a book critiquing genetic determinism with her son, Elijah Wald, titled Exploding the Gene Myth: How Genetic Information is Produced and Manipulated by Scientists, Physicians, Employers, Insurance Companies, Educators, and Law Enforcers. She was also a contributor on early editions of the book Our Bodies, Ourselves.

“She was an important mentor for so many women, and we were honored to have her as our friend and colleague,” said Judy Norsigian, co-founder of the Our Bodies Ourselves non-profit group.

In 1952, Hubbard earned a Guggenheim fellowship at the Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen. Hubbard and Wald together won the Paul Karrer Medal in 1967 for their work on the photochemistry of vision.

Hubbard is survived by her son Elijah Wald, her daughter Deborah Wald, her foster brother Benjamin Goldstein. and two grandsons, Ezekiel and Oliver.

Boston Globe, PDF (Monday, September 5, 2016),

Harvard’s Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality

Ruth Hubbard: Her Life and Work (Harvard Symposium, June 2, 1990)

Obituary on Marine Biological Laboratory